Ecommerce: Flow cross-selling

Inspired by apps like Foodcourt, Chowdeck, and Eden, I will be writing some essays on E-commerce in Nigeria over the next few weeks. The first part, which you are reading now, deep-dives into the current state of food delivery and focuses on a critical missing piece in the online food shopping experience that players must strongly consider implementing.

I will use three companies as reference points for this article: Eden Life, Chowdeck, and FoodCourt. They are relatively similar in terms of age, business model, and target location.

First, a little bit about all three companies.

FOODCOURT vs. CHOWDECK vs. EDEN

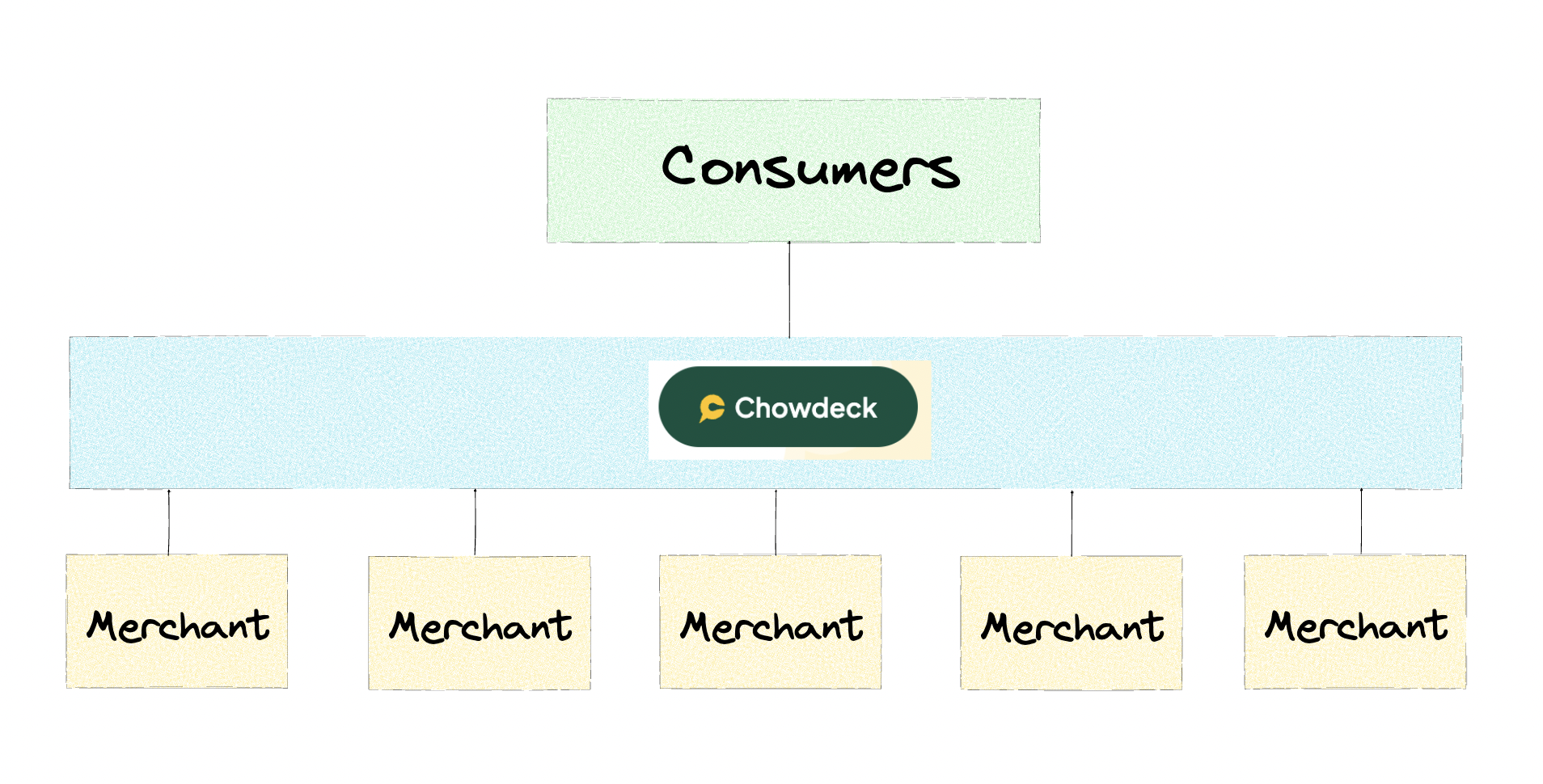

Chowdeck styles itself as a “logistics company” running an aggregator food delivery model. It allows restaurants to list and sell their food via its mobile app. The restaurants own the food production, while Chowdeck handles deliveries. The central piece to this model, however, is that Chowdeck owns the customer relationship—never the merchant, and the supply side is commoditized.

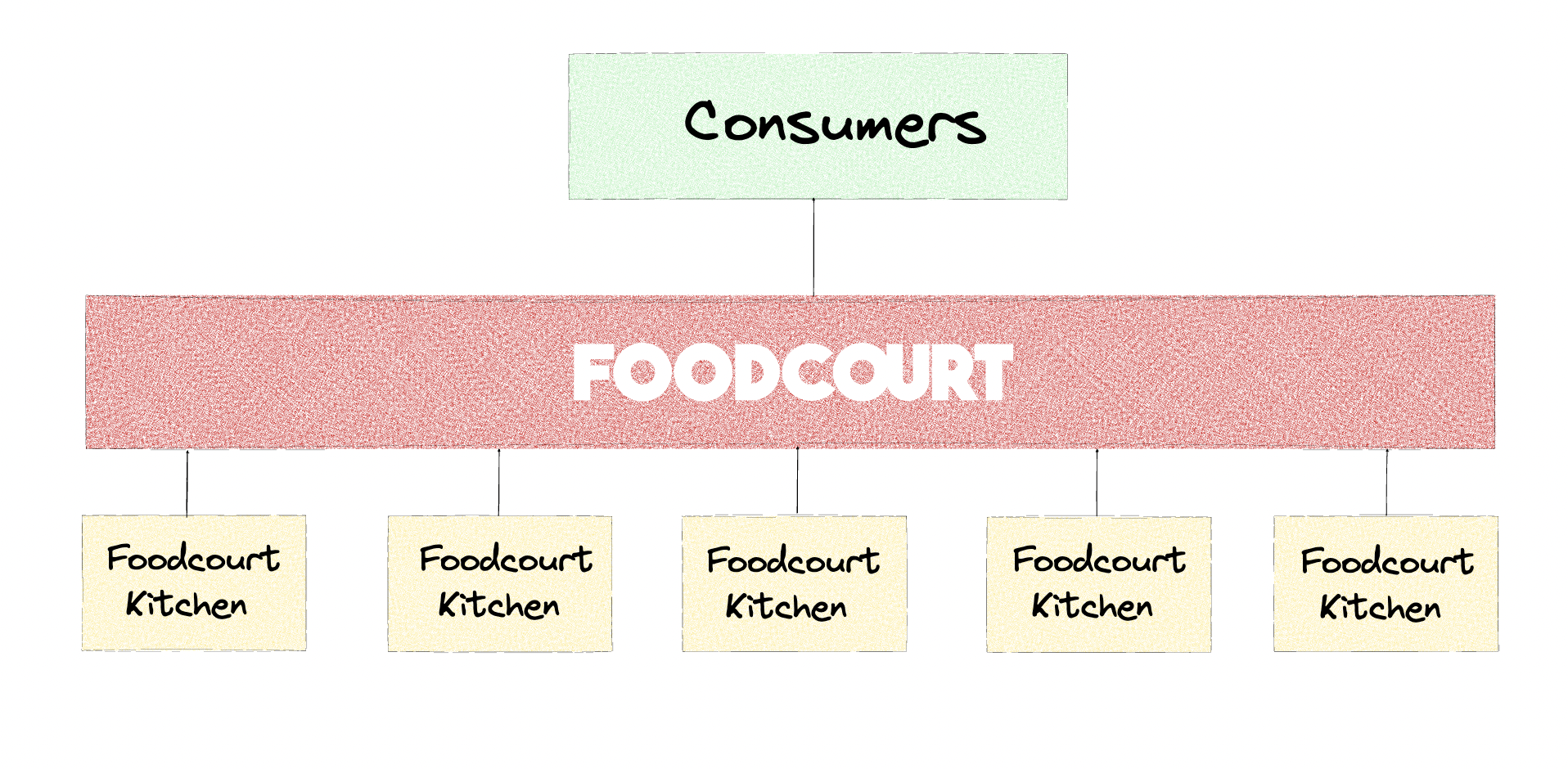

Foodcourt, on the other hand, operates as a dark kitchen. Although its app lists multiple stores, all listed stores are owned and managed by the company. This allows for better quality control and optimizations in the meal creation process. Since the company owns the supply and demand, it can give users a seamless & consistent experience while making more money. Their model looks more like this:

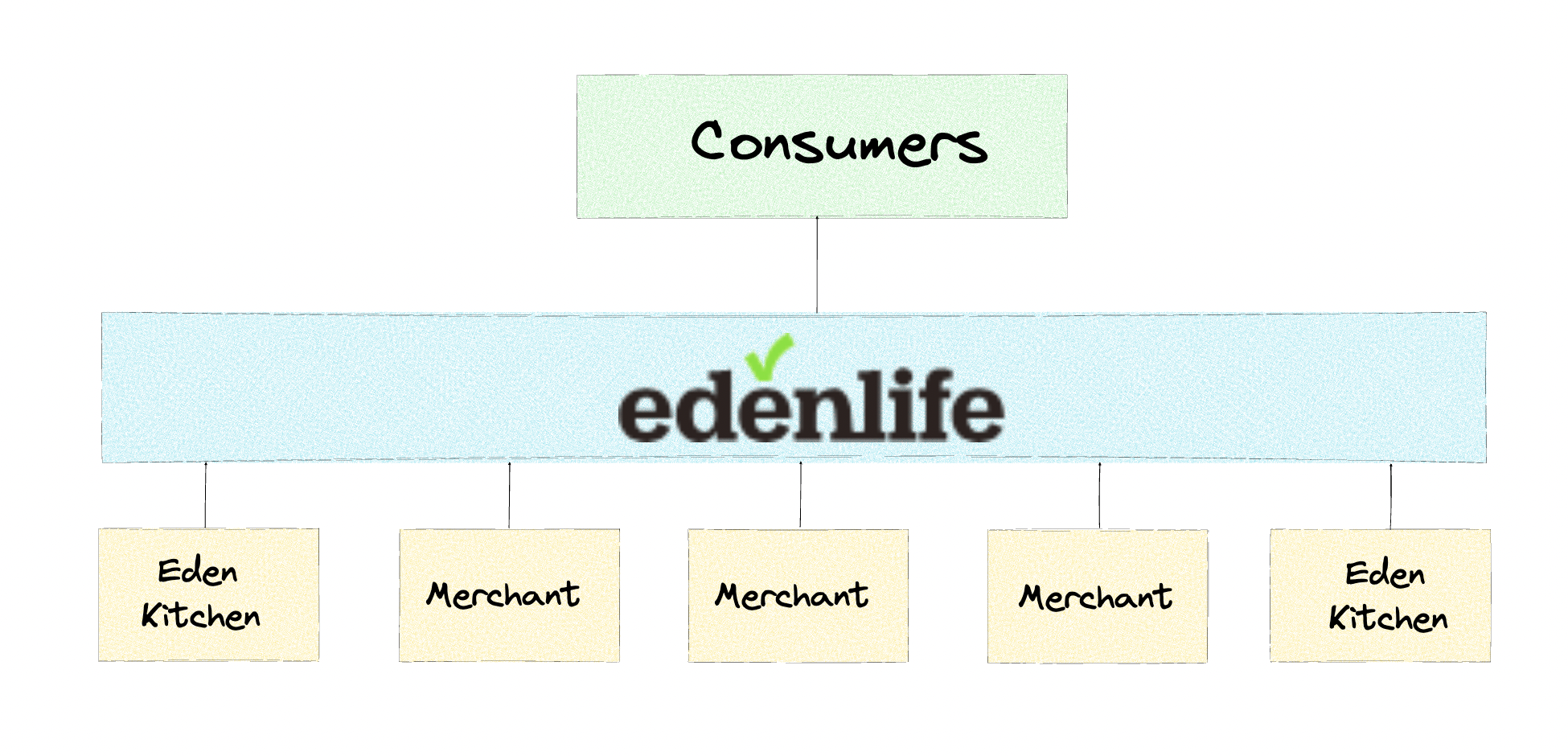

Eden, the final reference company, runs a mix of both models. Although it initially started as a digital concierge service for middle-class Nigerians, it has since pivoted into a food delivery service that makes its own food but also allows other restaurants to list and sell via its mobile app. However, like Chowdeck, Eden owns the customer relationship—never the merchant.

One way to observe how these businesses see themselves is this: Eden is listed as a merchant on Chowdeck while still offering a rival service on its mobile app.

PULL VS PUSH COMMERCE

All internet services can be categorized based on two types of user actions: Pull and Push.

Google is the perfect example of a pull service. Users are actively looking for a particular piece of information or an answer to a specific question, and Google’s search engine lets them pull that information.

Facebook, on the other hand, is a typical push service. User behavior is much more passive since users don’t have to actively ask for information. Instead, Facebook automatically pushes the most relevant content into their newsfeed. In Push services, the user uses the internet in a passive way, and content comes to them.

Cross-selling: the key to unlocking more revenue

There are many tactics e-commerce businesses can employ to boost revenue. One option is to spend more money and effort into driving higher volumes of traffic to your application. However, a second, more often more efficient technique, is to use cross-selling. Rather than constantly trying to generate new leads, cross-selling allows businesses to generate more value from existing shoppers and customers, thereby increasing profits.

Cross-selling is a sales technique used to get a customer to spend more by purchasing a product related to what’s being bought already. It involves offering an additional complimentary product. It is not to be confused with upselling, which involves trying to sell a customer a more expensive item or upgrade.

From a product and UX standpoint, there are two ways to do cross-selling: curiosity or flow.

Curiosity cross-selling

As the name implies, this method of cross-selling relies on the curiosity of users to get them to use additional services. In some sense, it is a pull service, placing the burden of discovery and intent on the customer. It’s a gentle invite saying, “Here is this other product we offer. We hope you notice it someday. Come check it out whenever you feel like it.”

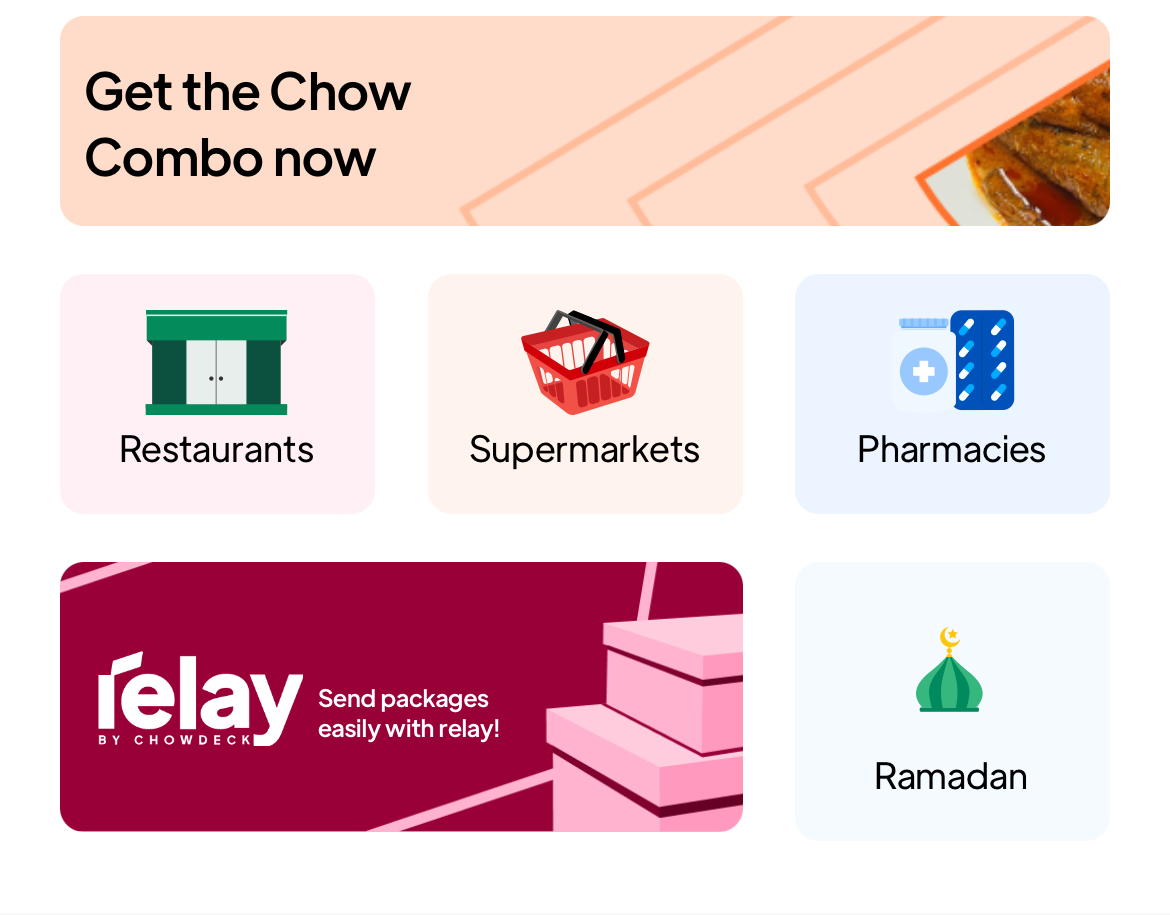

Curiousity cross-selling is typically achieved by selling complementary product categories at distinct, predictable points on the website or app, typically at the beginning of the user journey or on the home screen.

A good example of this can be found on the Chowdeck app. Although the logistics company is popularly known for its food delivery service, it has a number of other offerings including pharmacy, grocery, and last-mile deliveries. All these services are represented by distinct sections and icons on the home screen.. However, for the average customer ordering food, these services are completely unrelated to what they set out to achieve when they open the app.

Eden takes a similar approach with its additional offerings like supermarket orders, drinks, and cosmetics.

However, this approach's limitations become apparent very quickly. The dedicated sections for cross-selling represent how the products look internally to the business, not to its users.

People don’t open an app and then think, “Hmm, do I want quality groceries or instant grocery, or do I want to do online shopping?” Users mostly open apps when they want to solve a problem. And they always open the first app associated with the solution to that problem in their mind. For all of Chowdeck and Eden’s bets to work, its users need to think of it across a range of purchase scenarios. This is hard, if not impossible.

Curiosity is just one way to build a cross-selling service; however, it remains the most popular way for most e-commerce businesses. The reason is that it is much easier to build, spin up, or wind down. It’s an easy option for companies and product managers who want to experiment quickly with new verticals.

All you need to fight for is real estate on a primary screen, which then takes the user into whatever you’ve built in a sandbox. For most conservative, risk-averse companies, new product developments are crammed into curiosity cross-selling experiences.

Flow Cross-selling

The other way to cross-sell is by flow—which cross-sells products to users dynamically across their journey. In flow, the app is optimized to let users do exactly what they set out to, deftly positioning new offerings that trigger unintended but complementary behaviours in them. It edges out curiosity-cross selling because it can be used to both introduce new products and increase the average order value of existing offerings.

In some sense, it is a push service. Users don’t ask for it, yet it is presented to them. It says, “Based on your current journey, I think you should know about this offering. It may be great for you. You don’t have to use it now, but if you do, it may improve your experience.”

Ubereats does this perfectly. If you head to the Ubereats website to buy Chicken, just before you checkout, you get a pop-up page asking if you’d like some fried rice or Pepsi as well. Up until that moment, the user may never have considered anything other than chicken, but an offering presented at the right time allows them to maximize their experience and generate more value for the business. That is flow cross-selling. Even if the user ends up not making an additional purchase, a new model has been created in the user’s mind. Ubereat’s service is not yet available in Nigeria, but it provides context on what may be possible.

All e-commerce apps and websites combine curiosity and flow cross-selling, but the distinction of when to do what and where reveals a lot about the company itself. And that’s because both come with their advantages and trade-offs.

Building Flow cross-selling experiences requires a different way of thinking because it requires more conviction—both in the product and experience. You need to know what you want to surface at which point to your user and be completely convinced that it’ll work.

It also requires much greater alignment inside an organization because placing things on a regular path intersects with the objectives of several teams, and all of them need to be onboard. If it doesn’t work, you’ll also need an exit strategy. It requires a lot of creativity and conviction.

The choice between curiosity and flow cross-selling depends on different factors, but the biggest reason curiosity cross-selling fails is that it places the burden of association on the user. It also has no impact on users' average order value, even though it may eventually impact customer lifetime value.

Flow cross-selling is slow and deliberate, but it’s also sticky. The user association journey is generally continuous and involves constant education. A user opens Chowdeck to buy Coke, and at some point, she notices that they are offering grocery products. A few days later, they remembered they needed some milk. Instead of going to a grocery delivery service, they decide to try out Chowdeck. A few weeks later, while buying groceries, Chowdeck suggests some pharmaceuticals. They may not have known that the company offered pharmaceuticals. Shortly after, they offer deliveries. “Chowdeck does delivery? Ooh, Wow.” They can now send their clothes to the laundry. Boom!

That’s new consumer behavior in action.

How to build a flow-cross-selling service

There are three main points in the user journey where businesses can implement cross-selling:

Precheckout cross-selling

Flow cross-selling can be implemented at the pre-checkout stage, where shoppers are still browsing. This is one of the easiest to build because the user’s flow is not interrupted while they are shopping. It can be done by building out complementary items and promotions.

Cross-selling during checkout

Checkout is another point of the user journey where flow cross-selling can be implemented. Once shoppers have added their items to their cart and are about to complete their purchase, businesses can recommend products, giving buyers the opportunity to discover new products that they may be interested in and, in turn, increase the total purchase amount.

Post-checkout cross-selling

Finally, e-commerce cross-selling can be done post-checkout, i.e., after a customer has completed a purchase. This technique can promote new business lines based on what users have already purchased.

Conclusion

Flow cross-selling can be an important revenue driver for businesses in slim-margin industries outside of E-Commerce. Neobanks, for instance, can prompt users to save a percentage of funds received when they exceed a certain threshold or nudge them to opt into an auto-debit service for monthly bills. The complexity required to build is a challenge, but for many African tech businesses, the potential increase in customer lifetime value can provide a significant push towards sustainability.

Do you have feedback or thoughts on this post? If so, I’d love to hear them via my email at the bottom of the blog.

Thanks to Prince, Ahmed, Damola and OJ for reading drafts of this post

You can read the full version of this here.